Discovering Robert Flaherty

and Rob Rombout:

A Director’s Story

by Julee Laporte

Nearly sixty years after the release of Robert Flaherty’s Louisiana Story, Belgian director Rob Rombout along with a cast of thirteen students and countless natives return to Flaherty’s unquiet swamps in w, a collective endeavor intended to re-evaluate and re-discover the heart of an often misrepresented people. In the quasi-alchemical transformation which occurs in all cinematic enterprises, Flaherty and Rombout disappear, for the most part replacing their proper voices with celluloid images and regional testimony. However, it is clear that documentary film does not completely remove the director’s presence, and traces of their ambition and inspiration can be seen throughout their work. How then are we as both spectator and supporter supposed to find Flaherty and Rombout, as well as their respective “found stories”? To what extent did these men and their tales unconsciously and inconspicuously influence one another and their respective audiences? Through an analysis of their sometimes divergent but often shared methods of approach, discovery, and communication, it is perhaps possible to arrive at a more developed understanding of the role each played in shaping our own vision of Louisiana and its myriad stories.

« It is clear from his work in Perm-mission and Revisiting Louisiana Story alone that Rombout takes great pleasure in allowing people he finds (often literally) on the streets to help compose his own story. »

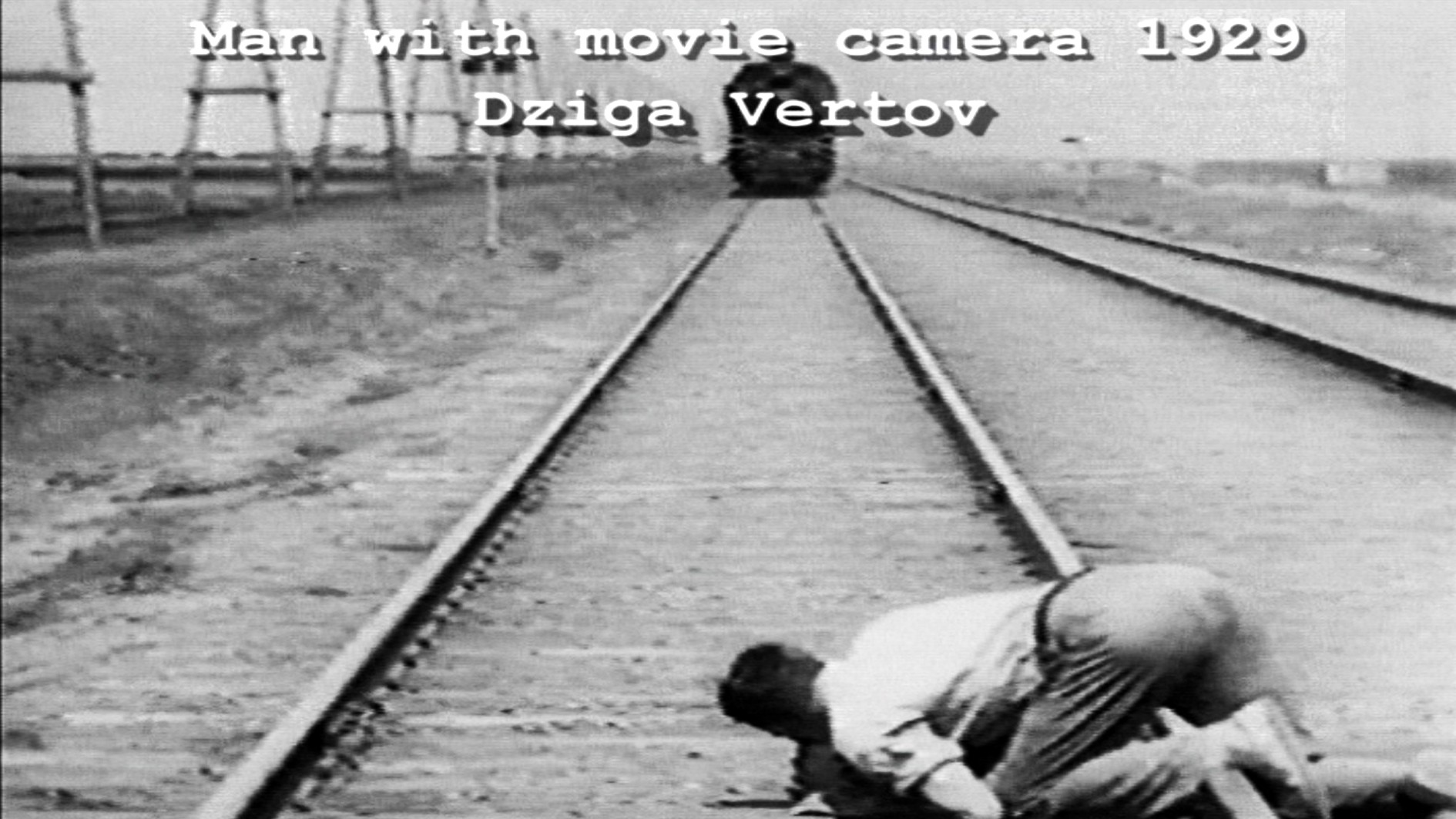

Nearly half of a century before the advent of French New Wave and similar movements in mid-century cinema, Robert Flaherty first fled the studio in search of what he called the found story. Hoping to escape forced dialogue and kitschy lot scenery, Flaherty traveled to the far reaches of the world in an attempt to capture on film those moments which defy re-creation in their singularity and must therefore be allowed to unfold in front of the lens. This is not to say that Flaherty never had a hand in hurrying this process along by modifying the natural ebb and flow of a community during a shoot. While not professional actors, the characters listed in Louisiana Story as “The Boy,” “His Father,” and “His Morther,” were certainly not a real family. Familial ties were forced in order to support the larger story, what Flaherty considered to be the bigger picture: a cinematic presentation of the Louisiana landscape stunning in both its beauty and magnitude. Flaherty remains true to the objective aims of documentary in that he provides the audience with countless opportunities to enjoy panoramic views of lush wilderness, letting the camera rest on a single bird in a tree for minutes at a time. While montage is also employed to give the audience a sense of action and plot movement, Flaherty often allows the image to develop at its own pace, resulting in some of the most beautiful film ever taken from Louisiana swamps. As a Russian enthusiast of Flaherty remarked at the annual Flahertyana documentary festival, “It seems very characteristic of Flaherty to rely less on montage. The less you cut, the less you lie, and the better the film will be [1].” Flaherty’s mise-en-scene gives the found story its depth and purpose while functioning as the perfect vehicle for relating the grandeur of Nature and its delicate relationship with human-life in south Louisiana.

Following in the footsteps of Flaherty, Rob Rombout also left the confines of the studio, after years of directing commercials for various European broadcasting agencies, and devoted himself to documentary film. Unlike Flaherty’s unwavering attention to countryside and swampscapes, however, Rombout uncovers his found story through a plethora of diverse sources not limited to natural phenomena and often including metro stations, bathrooms, international film convocations, and regional festivals. These locations rarely take center stage by their own accord, though; Rombout typically uses them as a backdrop for what appears to be a much more important component of to his method: different people and their own found stories. It is clear from his work in Perm-mission and Revisiting Louisiana Story alone that Rombout takes great pleasure in allowing people he finds (often literally) on the streets to help compose his own story. For example both the train attendant in Perm-mission and the egg dyers in Revisiting Louisiana Story contribute greatly to their respective films, one non-verbally communicating the frigid cold of near-Siberian Russia and the others cheerfully providing a bounty of humor and anecdotes from their mental registry of Cajun culture. Here Rombout fulfills his obligation as a documentary filmmaker, much like Flaherty, in allowing the camera to seize these moments and then rendering them to the audience with as little interference from the man working behind the machine as possible. Through his work it is clear that Rombout’s found story is not his alone. With the collaborative efforts of thirteen student filmmakers in Revisiting Louisiana Story, the final found story is an amalgamation of all those stories that passed before the lens and they who helped to tell them.

The found story of both Rombout and Flaherty is only possible given its distance from the director’s normal environment. In leaving the studio, Rombout and Flaherty condemned themselves to the life of a perpetual outsider, never completely at home with any of their subjects but always made to feel welcome nonetheless. Flaherty seems to have developed rather strong ties with the locals during the shoot for Louisiana Story because his work is still celebrated to this day in many of the areas surrounding Bayou Petite Anse. The same can be said for Rombout’s voyage to Perm, Russia, where he was granted the esteemed honor of filming an assembly of filmmakers at work. While it is certain that the role of outsider introduces an array of difficulties, from gaining the trust of a community to finding a decent place to lay your head, it also supplies our directors with a perspective altogether different from that of the natives, thus allowing them to discover that which may remain hidden from an insider. This act of discovery encapsulates the very essence of the found story and serves to solidify the importance of the objective observer in documentary filmmaking. Through their collective works, Rombout and Flaherty heighten the process of discovery by allowing the voice of the insider to be seen and heard through the lens.

While both Flaherty and Rombout may arrive at the discovery of their found stories through similar methods, the ways in which they communicate them to the audience are very different indeed. In an article published recently after the release of Louisiana Story in local newspaper, Gene Yoes, Jr. highlights one of Flaherty’s most acclaimed techniques: The child was fondling his new rifle that his father had bought in the city. His pet raccoon, which he thought had been devoured by the alligator, returned. The child dropped his new rifle and went to his coon. “Told” without the use of dialogue, this sequence powerfully shows the child as he rejects the mechanized world, the artificial world created by machinery, and returns to his native environment… [2]”.

As the insider approving the work of the outsider, Yoes brings to light Flaherty’s reliance on non-verbal communication as a means to convey the relationship between the past and present as well as technology’s powerful influence on traditional ways of living, two rather important messages in Louisiana Story. Documentary film for Flaherty requires a certain respect for the audience as well as the subject, and while the child in the film was acting out a role that was not his own, Flaherty did not attempt to sway the audience with an eloquent speech on the evils of industry and the importance of retaining time-honored customs. Rather, he allowed the child’s interaction with what we could consider to be an extension of his native land, the raccoon, to demonstrate that the arrival of the oil derricks did not change everything, that the boy’s way of life would not suffer drastic change as had been previously thought. Witnessed also in the magnificent scene aboard the derrick where the workers scurry around in an attempt to operate a rather complicated piece of machinery, Flaherty’s visual representation of exchange, change, and growth transmits his sense of discovery in a way that surpasses the sometimes unnatural use of language and dialogue in film.

Rombout, on the other hand, takes full advantage of what Flaherty leaves out, as he often uses his own words to voice-over images on the screen and will conduct extensive personal interviews from behind the camera. Indeed it is much easier to find Rombout in his films that in it is to find Flaherty in his, if only because Rombout seems more aware of his position as a documentary filmmaker and is able to communicate this knowledge openly to his audience. This presence is almost palpable in the student films of Revisiting Louisiana Story, where Rombout never acts as director but assumes an important role as guide and teacher. It is as if Rombout, the student-directors, and we the audience are discovering Cajun culture at the same time, as if Rombout’s struggle to understand and relate his story is the story that we see. It seems that Rombout chooses to inject himself into his films in order to remind us, and perhaps himself, that he is still there, that documentary film is never purely objective because it is always subject to the multitude of decisions made by the filmmaker each day. However, in unabashedly presenting himself to the camera, Rombout is attempting to undertake a more honest approach to documentary film, revealing himself to all so that we might better understand the process as well as the product.

« Rombout works to uncover what exactly in Flaherty’s approach has influenced so many people over decades and across national borders. »

No clearer example of this directorial awareness can be found than in his film Perm-mission, in which Rombout travels to the small village of Perm, Russia to film a documentary about Flahertyana, the annual festival dedicated to promoting the legacy of Flaherty and preserving the integrity of documentary film in the country. Through his conversations with various directors and festival-goers, Rombout works to uncover what exactly in Flaherty’s approach has influenced so many people over decades and across national borders. We see Rombout toiling alongside the subjects of his own documentary as together they examine everything from different techniques in cinematography to choices in editing and general storytelling, in hopes of arriving at a better understanding of why Flaherty’s films still stand today among the best in the genre and how they as filmmakers can learn from his talent. A possible answer to these questions can perhaps be found in one Russian filmmaker’s attempt to explain the magic of documentary: “The story must serve as a beginning and carry along with it the desire to share, the desire to share a bond of reciprocity so that there might be a mutual exchange between the author, his vision of things, and the spectator [3].” Here Rombout and his subject touch at the very core of documentary film, especially the kind undertaken by Flaherty. While establishing relation with the members of Flahertyana and the films of Flaherty himself, Rombout also presents to the audience his own personal relationship with the documentary, allowing us as he did in Revisiting Louisiana Story to witness the steps taken to arrive on the big screen.

While it is clear that both Flaherty and Rombout attempt to make known this relationship between the story, the author, and the audience in all of their films, many have accused Flaherty of falling under the influence of subversive powers during the making of Lousisiana Story, most notably that of the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey. Standard Oil commissioned the film as part of an elaborate public relations ploy to boost the company’s image. Flaherty’s critics claim that the film’s somewhat tidy resolution of the conflict between the oilers and the inhabitants of the area was influenced by the support he received from Standard Oil. Often in cinema the line between documentary and propaganda becomes blurred once a benefactor’s interests clash with those of the director. However, it would be difficult to claim that Flaherty allowed Standard Oil to alter the direction of his film, considering that their name and logo did not appear in the credits or elsewhere. Some are nonetheless troubled by what they see as an over-simplification of the sordid relationship south Louisiana has had with the oil industry. While the film does appear to carry a rather significant political in support of the oil industry, we should not forget that Louisiana Story is essentially a coming-of-age story about a boy as he begins his journey to manhood and struggles with the changing world around him as well as with the changes in himself. From his choice of shots down to his magnificent treatment of the Louisiana landscape, we can say with some degree of certainty that Flaherty himself was more concerned with telling little Joseph Boudreaux’s tale than that of the drillers.

What impact then did Standard Oil have on the way Flaherty told his Louisiana Story? Like in all artistic mediums, an audience’s attempt to understand a creator’s decision often ends in futile speculation. However if this questioning leads to hands-on cinematic investigation, as it did for Rombout and the student filmmakers, then it can also be a useful tool. Revisiting Louisiana Story was considered by many of the student filmmakers as their opportunity to address the issues raised by the sponsorship of Standard Oil, as well as other concerns involving Flaherty’s treatment of Cajun culture. Many modern-day Cajuns see Flaherty’s portrayal of their not-so-distant relations as an over-simplication of a rich and colorful people, reduced on the screen to an uncultivated, shoeless race of trappers and hunters. As mentioned by one of the student filmmakers, many Cajuns at the time of Louisiana Story had left the bayou in search of jobs in the city and were far removed from the somewhat primitive lifestyle depicted in Flaherty’s film. Where can their story be found in Flaherty? With Revisiting Louisiana Story, the student filmmakers were able to present their own collective found story through the telling of their unique and individual stories, reflecting both inside and outside perspectives and questioning the “objective” nature of documentary film. And far from denying the validity of Flaherty’s tireless struggle to understand the cultural and natural landscape that he found in Louisiana, Revisiting Louisiana Story serves to actualize documentary’s insistence on the relationship between the story, the director, and the audience by adding their own tale to the mix.

« Rombout and the student-filmmakers, each in their own personal homage to Flaherty, allow us to see Flaherty in a different light, as the camera turns around to face its author, analyzing his work, his dreams, and his aspirations. »

From Flaherty’s found story in Louisiana Story to Rombout’s attempt to grapple with this story in Revisiting Louisiana Story, both films afford the audience with an opportunity to draw their own conclusions as to the endless array of questions that may present themselves from even the most amateur study of Cajun history and culture. From their similar methods of approach to their mutual understanding of the genre, Flaherty and Rombout share much in terms of their appreciation and love for documentary film, and it is through these relations that we may come to truly see the Louisiana story given by each. While few, their differences serve to highlight the diverse influences and implications of the documentary, and furthermore strengthen its claims to a search for honesty before and behind the camera. Rombout and the student-filmmakers, each in their own personal homage to Flaherty, allow us to see Flaherty in a different light, as the camera turns around to face its author, analyzing his work, his dreams, and his aspirations. Flaherty, in turn, never ceases to amaze his viewers with the sheer beauty of his creation, projecting for better or worse his own found story of Louisiana. Luckily for us there are questions still to be answered in the domain of documentary film; undoubtedly there will also be other films that attempt to examine themselves and their art with the same careful scrutiny observed by both Flaherty and Rombout in their exploration of a people who will also continue to inspire for ages to come.

[1] Perm-mission. Dir. Rob Rombout. DVD. Nota Bene, 1999.

[2] Yoes, Jr., Gene. “Premiere Film Uses New Technique to Tell Story of State Marches.” The Abbeville Meridional 5 Mar. 1949.

[3] Perm-mission. Dir. Rob Rombout. DVD. Nota Bene, 1999.